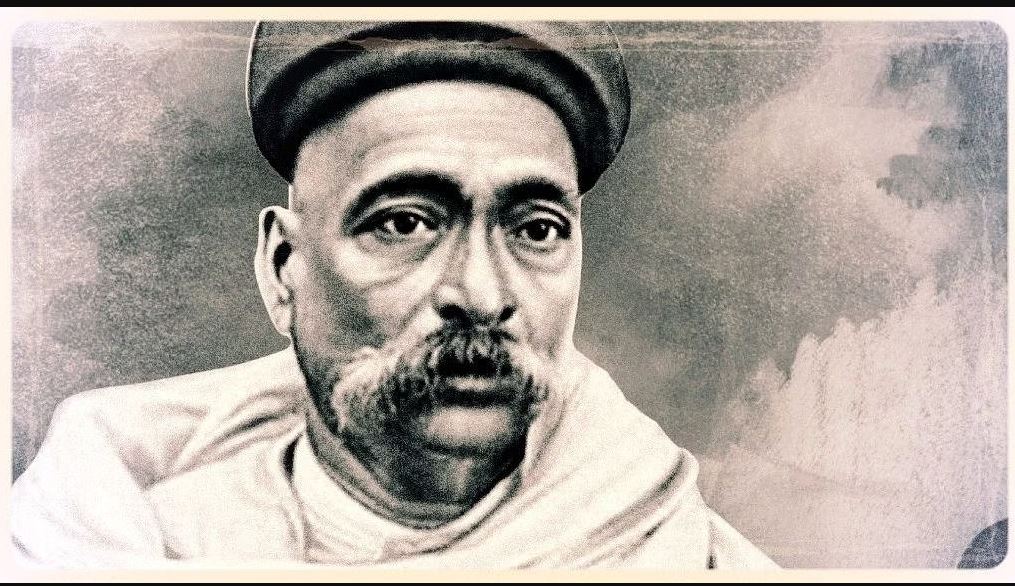

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, popularly known as Lokamanya, was born on July 23, 1856, in Ratnagiri, which is now in the state of Maharashtra, India. He passed away on August 1, 1920, in Bombay, which is now Mumbai. Tilak was a multifaceted individual, a scholar, mathematician, philosopher, and a fervent nationalist. His remarkable contributions laid the groundwork for India’s quest for independence by transforming his personal resistance against British rule into a nationwide movement. In 1914, he established the Indian Home Rule League and served as its president. During 1916, he orchestrated the Lucknow Pact in collaboration with Mohammed Ali Jinnah, fostering unity between Hindus and Muslims in their struggle for autonomy.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak Early Life and Career

Bal Gangadhar Tilak hailed from a cultured middle-class Brahmin family. Although he was born in Bombay (now Mumbai), he spent his early years in a village along the Arabian Sea coast in present-day Maharashtra until the age of 10. Subsequently, his father, an educator and grammarian, relocated the family to Poona (now Pune). There, Tilak pursued his education at Deccan College, earning bachelor’s degrees in mathematics and Sanskrit in 1876. He later studied law and acquired his degree in 1879 from the University of Bombay (now Mumbai). However, he decided to take up teaching mathematics in a private school in Poona, which eventually became the nucleus of his political journey.

Deccan Education Society

Tilak founded the Deccan Education Society in 1884, aiming to provide education to the masses, particularly in the English language, as he believed English could disseminate liberal and democratic values. Although the society called for selfless service, Tilak resigned upon discovering some members were pursuing personal gains. He then turned his focus towards awakening political consciousness through his ownership and editorial control of two weekly newspapers—Kesari in Marathi and The Mahratta in English. Through these publications, he gained prominence for his sharp critiques of British rule and moderate nationalists advocating Western-style social reforms and constitutional political changes. Tilak asserted that efforts towards social reform could divert energy from the larger struggle for independence.

Nationalist Movement

Broadening the Nationalist Movement Tilak aimed to broaden the reach of the nationalist movement, which primarily involved the upper classes at the time. To achieve this, he incorporated Hindu religious symbols and invoked the Maratha tradition of resistance against Muslim rule. He organized significant festivals, such as Ganesh in 1893 and Shivaji in 1895. These festivities resonated with the public, but also raised communal tensions.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak Challenges and Imprisonment

Tilak’s activities stirred the Indian populace, but they also led to conflicts with the British government. In 1897, he faced charges of sedition, leading to his imprisonment for 18 months. During Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905, Tilak endorsed the Bengali demand for partition annulment and advocated boycotting British goods, sparking a nationwide movement. In the following year, he presented the Tenets of the New Party, advocating passive resistance as a means to break the influence of British rule.

Indian National Congress

Tilak’s ideology clashed with the moderate Indian National Congress, which sought gradual reforms. His call for swarajya (independence) caused a division within the Congress Party in 1907, leading to his prosecution once again. He served a six-year prison term in Mandalay, Burma (Myanmar), during which he penned his magnum opus, the Śrīmad Bhagavadgitā Rahasya, offering an unconventional interpretation of the Bhagavadgita that emphasized selfless service.

Continuing Activism and Legacy Released in 1914

Tilak resumed his political engagements, establishing the Home Rule League with the resounding slogan “Swarajya is my birthright and I will have it.” He also rejoined the Congress Party and signed the significant Lucknow Pact in 1916, uniting Hindus and Muslims. During a visit to England in 1918, he forged connections with the Labour Party, foreseeing its influence on India’s future.

Tilak’s return to India in 1919 marked his shift towards a more cooperative approach, advocating “responsive cooperation” with the legislative council reforms. Regrettably, he passed away before fully realizing this vision. Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru hailed him as a maker of modern India and the father of the Indian revolution, respectively. Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s enduring legacy remains a cornerstone of India’s struggle for independence and its journey towards self-governance.

Download App

Download App